Letters | What young humans can do that AI can’t

Readers discuss how the education system must adapt to the advent of generative AI, and the use of the p-value in determining statistical significance

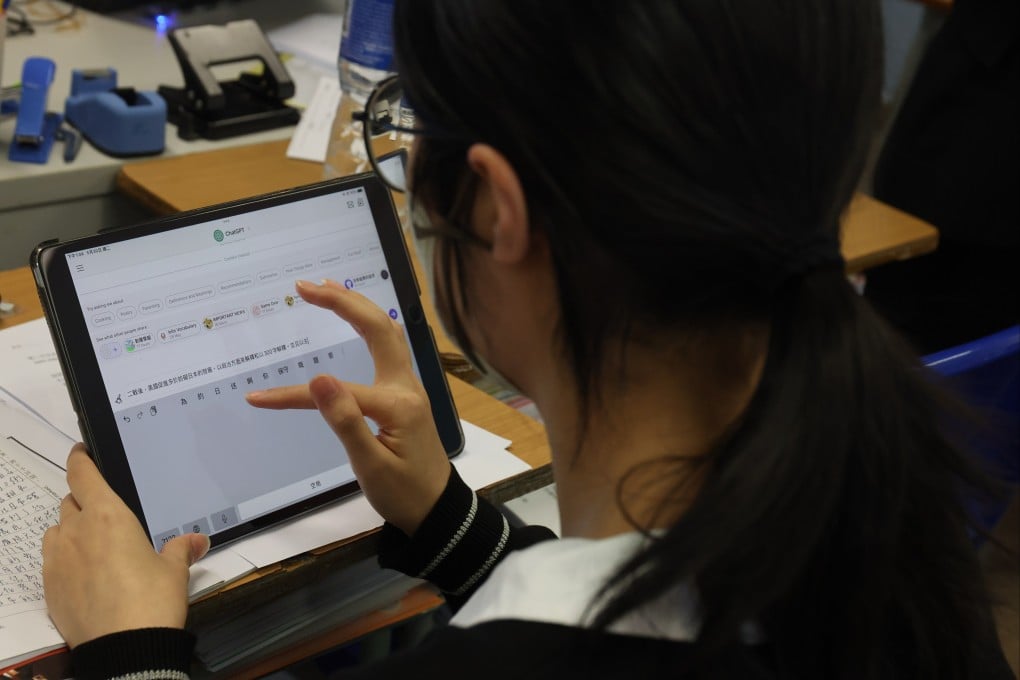

But ethical training is not enough. A recent study reports that about 40 per cent of secondary school students admit to using AI to cheat. The actual number is almost certainly higher. It is naive to expect that an honour code alone will dissuade students from such rampant improper applications of the internet.

Instead, society’s modes of teaching, learning and assessing learning need to change fundamentally. Teachers must study what skills artificial intelligence (AI) makes redundant and then alter, evolve or otherwise eliminate their pedagogy in these areas. We must likewise focus attention on the skills that large language models lack.

AI is not omnipotent – far from it. ChatGPT struggles to form value judgments (good and bad, better and worse) that it is willing to defend. When asked about the pros and cons of allowing the use of AI in English classrooms, for example, ChatGPT cautioned me that the issue was “complex” before producing a judicious analysis of costs and benefits.

At the end of the response, the tool offered a “possible middle ground”: teaching students to use technology moderately. I then prompted the bot to evaluate which of its arguments was “the best”. Here was its final answer: “Rather than taking a strict ‘for’ or ‘against’ stance, the strongest position is a balanced approach. Students should be taught to use AI as a tool. Schools should emphasise AI literacy.”

This “balanced approach” is typical of artificial reasoning. ChatGPT cannot make exclusive binary decisions in which, like the choice faced by poet Robert Frost’s speaker in The Road Not Taken, following one path means rejecting another. This failure is likely due to the fact that AI is unwilling to be wrong or to accept responsibility for being wrong.