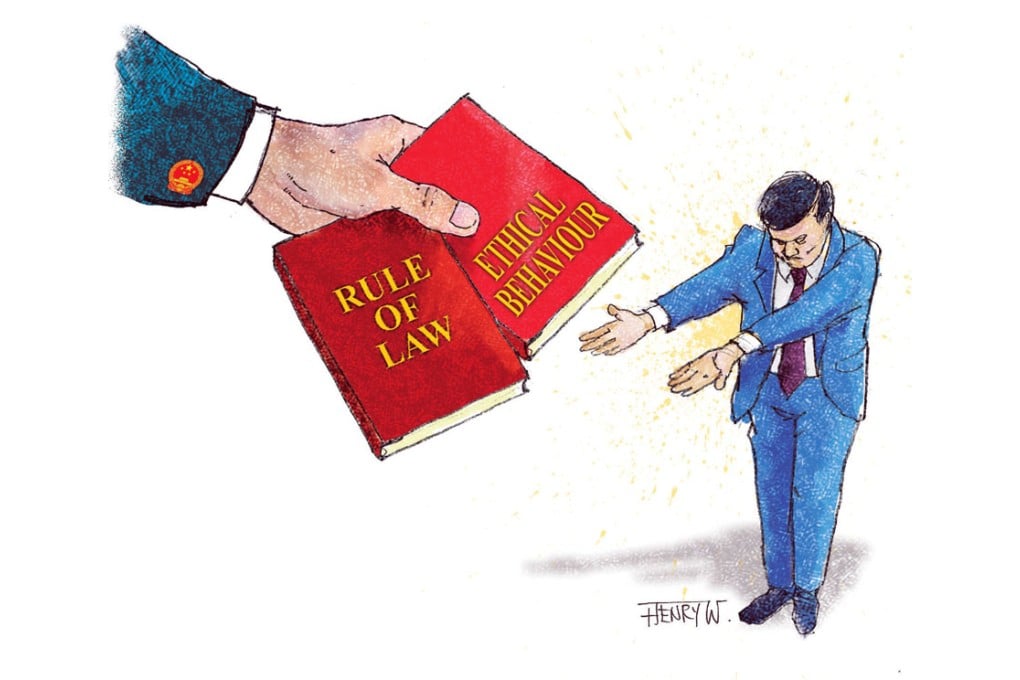

In China, the law and morality must work in tandem to contain party elite

Lanxin Xiang says Beijing's recent legal reform, when not coloured by Western filters but understood in the context of China's political history, is a groundbreaking effort to curb corruption

Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws has for more than 200 years led many in the West into believing that the tension in the Chinese political system is created by the lack of "democratic legitimacy" and the suppression of individual freedoms. This is a common misunderstanding based on ignorance of Chinese political history. Western observers tend to make a distinction between the "rule of law", Western-style judicial justice, and "rule by law", dictatorial rule by legal provisions, for example, Hitler's Nuremberg Laws.

It is not surprising that comments in the Western media on the Communist Party's recent fourth plenum were largely negative. However, the assumption that China only practises rule "by" law, rather than the rule "of" law, for the purpose of strengthening its one-party dictatorship, is too simplistic and misleading.

This argument overlooks the fact that the Communist Party has to align its interests with those of the people, or the regime will fall. This is because the Chinese people understand political legitimacy through Confucius' eyes, that is, they expect correct moral behaviour from the political elite. The party is no exception; thus, even its publicly declared principle of judging legitimacy is a kind of Confucian "deeds legitimacy", in the "spirit of morals", rather than a "procedural legitimacy", which is in line with the more mechanical "spirit of laws".

Clearly, not all the party elite put the people's interests above their own. The regime is rotten from within, as the unprecedented level of corruption and rent-seeking under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping , Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao showed.

The Chinese leadership is facing its biggest legitimacy crisis since 1949, at least in the eyes of the population. It is apparent that corrupt officials have successfully taken advantage of the flaws and loopholes in the procedures within the dysfunctional party disciplinary machine, the Byzantine state administration and the mafia-style judicial games.

After decades of inaction, the emperor of China was the only one who did not know that he wore no clothes. But the party's new generation of leaders refuse to be naked in the eyes of the public and wisely recognise that the party must repair its crumbling reputation through legal reforms, to enforce the party rules more efficiently by due procedure.

But, of course, the sense of urgency in the legal reforms is not motivated by creating Western-style rule of law. It is driven by the desire to restore the credibility of the party, deeply rooted in its glorious past and based on a popular belief that, as President Xi Jinping has argued, there are no party interests above the interests of the people.